Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| CASE STUDY: JetBlue Airways is on a fuel-saving journey using data analytics and pilot apps | Chris Lum, Director and System Chief Pilot, JetBlue Airways | View article |

| CASE STUDY: Amelia takes flight to reduce contrails | Adrien Chabot – Chief Sustainability Officer, Amelia | View article |

| CASE STUDY: From paper to digital charts at KLM | Emiel Snippert, EFB Project Manager / First Officer, KLM | View article |

| CASE STUDY: Breeze moves to AI-enhanced weather intelligence | Garrett Urry, Manager of Flight Dispatch, Breeze Airways | View article |

| CASE STUDY: Data-Led Fuel Efficiency | Luke Towler, Fuel Efficiency Systems Manager, Jet2.com | View article |

| CASE STUDY: Delta’s journey to a unified Content Management System | Jennifer West, Manager of Flight Ops Publications, Delta Air Lines | View article |

CASE STUDY: Amelia takes flight to reduce contrails

Author: Adrien Chabot – Chief Sustainability Officer, Amelia

Subscribe

Adrien Chabot – Chief Sustainability Officer at Amelia shares a program that has reduced contrails and their environmental impact for the airline

When we talk about aviation and sustainability, most people think about CO₂ emissions. But another, less visible factor has a big impact on the climate: contrails. At Amelia, we decided to take this issue seriously. What started as a simple question – can we reduce contrails in real operations? – has become a major part of our sustainability program. Today, Amelia is one of the first airlines to use daily contrail avoidance planning across its operations. Before explaining how we do it, here’s a bit of context.

AMELIA & AMELIA GREEN

Amelia is a French aviation group created in 1976. As figure 1 shows, we have about 500 employees and a fleet of 18 aircraft operating across Europe and Africa. Our activities cover scheduled flights, ACMI operations, charter services, and medical evacuations.

Figure 1

In November 2022, we joined IATA and signed up to the Fly Net Zero commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050. One year earlier, we had already launched Amelia Green, our internal program for all sustainability and decarbonization actions. Reducing contrails quickly became one of our main goals. With aircraft ranging from the Learjet 45 to the Airbus A320, our operations cover a wide range of altitudes and regions. That variety makes it more complex to optimize flights for climate impact – but it also gives us a good testing ground.

WHAT CONTRAILS ARE AND WHY THEY MATTER

Contrails, short for condensation trails, are thin white streaks formed when an aircraft flies through a cold and humid layer of the atmosphere. Hot exhaust gases from the engines mix with the surrounding air, causing water vapor to condense and freeze into tiny ice crystals — the visible trails we see behind planes.

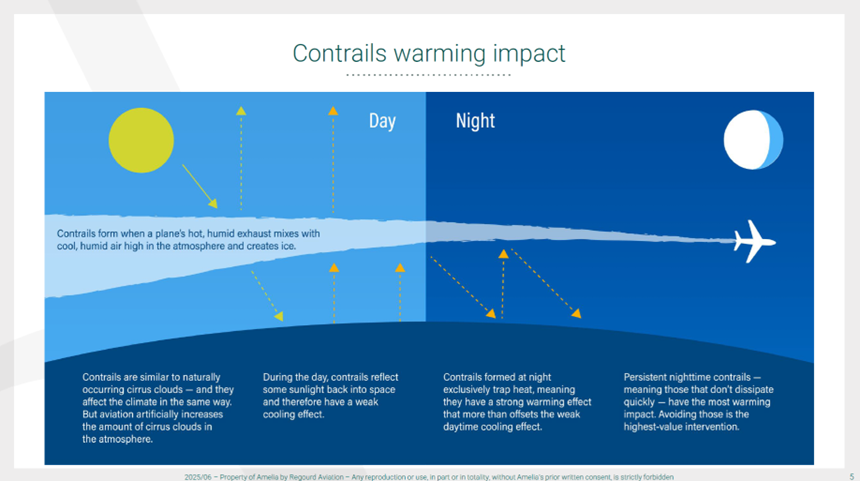

Sometimes, these contrails dissipate quickly. Under certain conditions, however, they spread and form thin cirrus clouds that can persist for hours. These clouds have a dual effect on the climate, as shown in figure 2: during the day, they reflect sunlight and slightly cool the atmosphere, while at night they trap heat, causing warming. On average, the overall effect is warming.

Figure 2

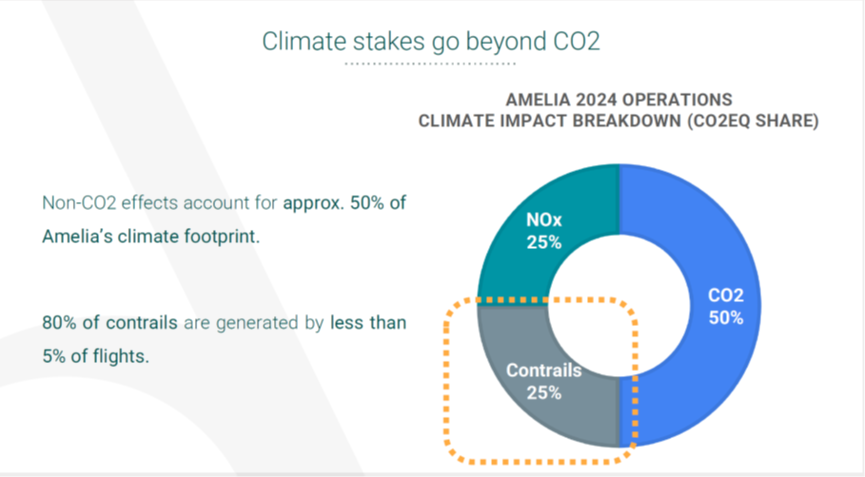

Scientific studies show that when contrails and nitrogen oxides (NOx) are included alongside CO₂ emissions, the total climate impact of aviation can be almost twice as high as CO₂ alone. Traditionally, CO₂ is the only metric airlines track, but for us, this evidence made it clear that contrail reduction had to be part of our climate strategy. Figure 3 illustrates the scale of the effect on our 2024 flights.

Figure 3

OUR NEW CHALLENGE: REDUCING THE IMPACT OF CONTRAILS

At Amelia, we decided to go beyond CO₂ tracking and address the full climate impact of our operations. Since 2021, we have run analyses to better understand non-CO₂ effects, including NOx emissions and contrails, both of which can significantly amplify warming. Considering both together, an airline’s total climate footprint can nearly double, making this a critical area for action.

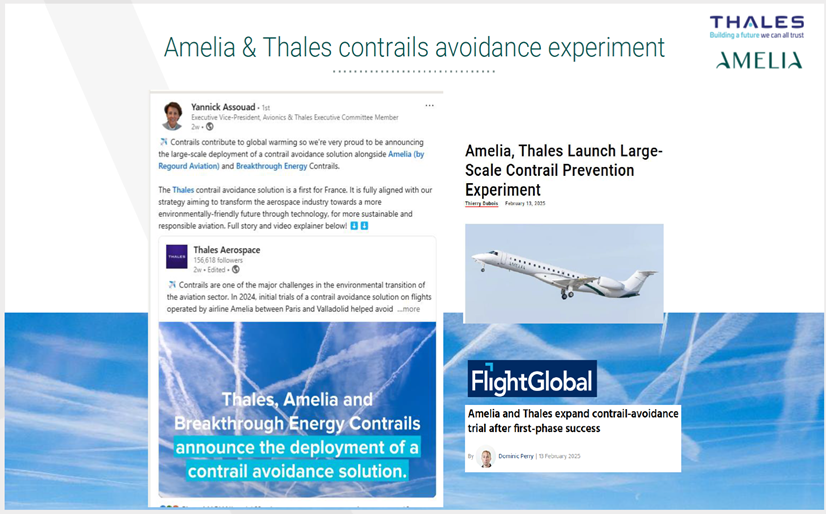

Analysis of our 15,000 flights last year revealed a striking pattern: 80 percent of the contrail impact came from just 5 percent of flights. While this trend is visible across the fleet, certain individual flights can have an even higher climate effect. In other words, some routes contribute disproportionately to contrail-related warming. To tackle this, Amelia partnered with Thales AVS, a company with deep expertise in aerospace and aviation systems. Thales develops tools for flight operations, navigation, and air traffic management, making them well suited to help us predict and avoid contrails.

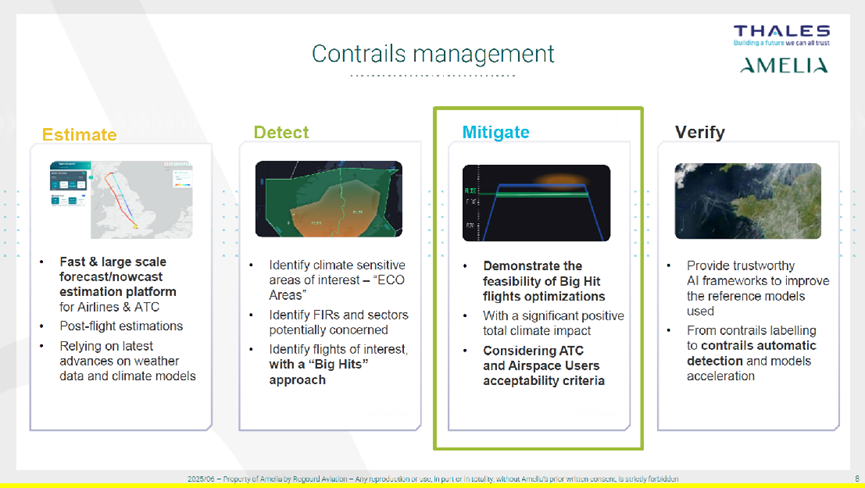

We started working with Thales in 2021 to develop a solution, see figure 4, that can:

- Predict where contrails are likely to form;

- Calculate alternative routes; and

- Help select the best option balancing climate impact and fuel efficiency.

Figure 4

User-centered implementation for maximum adoption and minimal workload

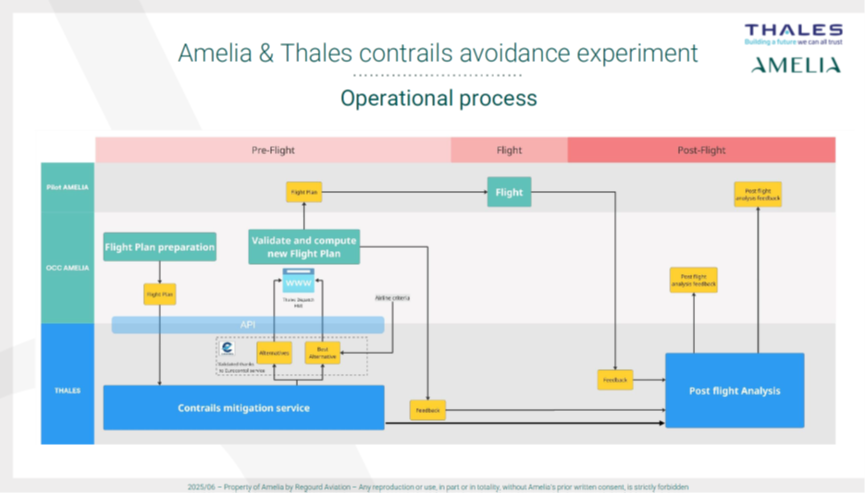

Managing contrail formation involves several steps, both before and during a flight as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5

The first step is to estimate the likelihood of contrail formation along the flight path. For this, we rely on weather forecasts to identify climate-sensitive areas, i.e., regions prone to contrails that we aim to avoid. We then assess how these areas intersect with planned flight paths to propose adjustments that minimize contrail formation.

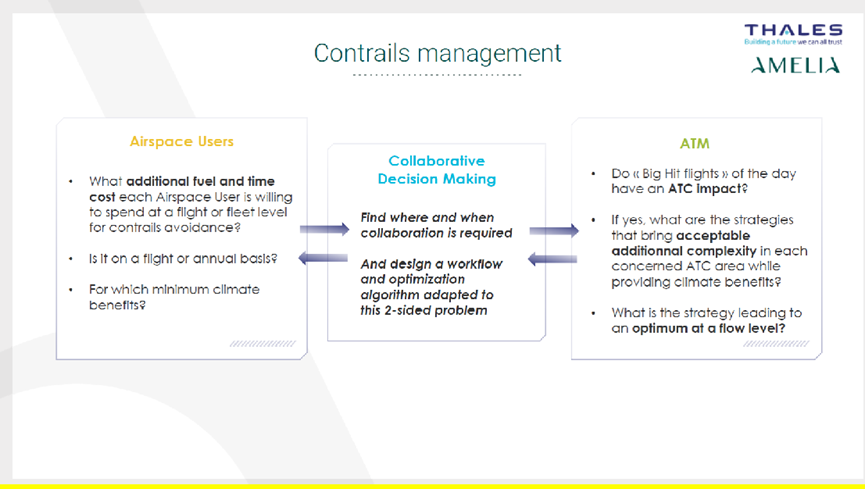

Not all flights produce contrails — only a small percentage do. Adjusting a flight path to avoid contrails may increase fuel burn, since flight plans are usually optimized for minimum fuel consumption. This means we must balance scientific accuracy with operational efficiency. There is also inherent uncertainty: contrails contribute to warming, but the exact effect is difficult to quantify. This uncertainty can affect operational procedures, particularly in-flight management by Air Traffic Control (ATC). For Amelia, which adjusts a few dozen to a few hundred flights, the impact is limited, but larger airlines would face greater challenges.

Figure 5

Our approach is collaborative and focused on the pre-flight phase, with potential adjustments during flight, in partnership with Thales. We analyze forecasts and determine how to provide ATC with the most efficient flight plan, as in figure 6.

Figure 6

During pre-flight, the Operations Control Center (OCC) prepares the flight plan and sends it to Thales. Thales identifies areas where contrails may form and calculates alternative routes that could reduce up to 40 percent of the total climate impact of a flight, within fuel limits (allowing 2 percent max extra fuel). In Europe, we update the previously filed flight plan with the new proposed route to check for conflicts. Once filed and approved, the OCC sends the optimized flight plan to the crew, along with a pilot briefing explaining that it is designed to avoid contrails. Feedback is essential. OCC teams report whether proposals were accepted and, if not, why not? Pilots provide post-flight analysis, allowing us to verify and continuously improve the process.

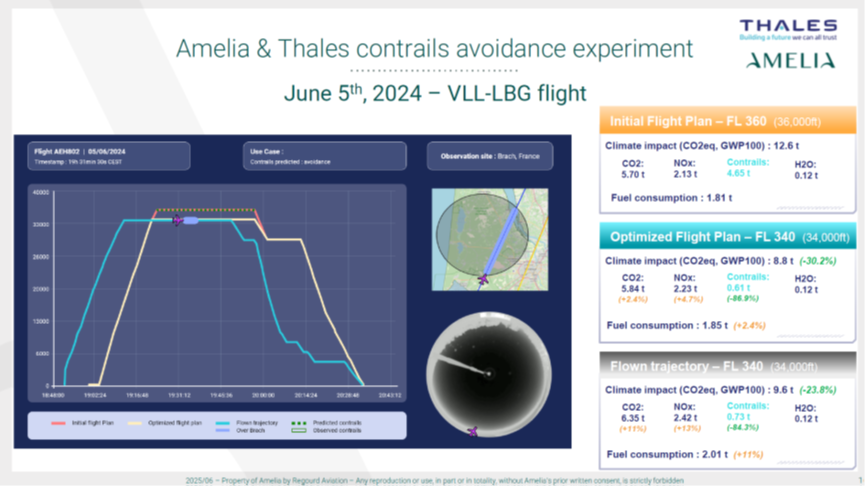

Initially, we tested a manual, in-house method before moving to an automated system. We evaluated vertical deviations, selecting flight levels to avoid contrail-prone areas, and measured the benefits in terms of both contrails’ reduction and fuel consumption. The first deployment of this approach started in June 2024, focusing on the Paris–Valladolid route , see figure 7. This route was ideal for testing due to its frequent contrails, allowing us to precisely determine the necessary adjustments.

Figure 7

CONTRAIL AVOIDANCE: FIRST RESULTS

We analyzed around 50 flights, including five dedicated test flights aimed at avoiding contrail formation. The results were encouraging: we saved about 15 tons of CO₂ equivalent from contrail avoidance for only around 100 kg of extra fuel burned. From a climate perspective, the results were clearly positive. This experimental phase allowed us to refine our methodology, develop the dedicated tool, and understand how the OCC and flight crews can collaborate effectively. These insights form the foundation for a systematic, long-term approach.

An example of the analysis is shown in figure 8 with the Paris–Valladolid route. The red line shows the original flight plan, the yellow line shows the alternative proposed by the tool, and the blue line represents the actual flight operated. In practice, departures rarely occur at the exact planned time or follow the same route, but this comparison helped validate our results.

Figure 8

On this route, we also worked with French company Reuniwatt, which provided images from an upward-facing camera to detect contrails along the flight path. While this covered only a 30 km segment, it provided additional insights that strengthened our overall analysis.

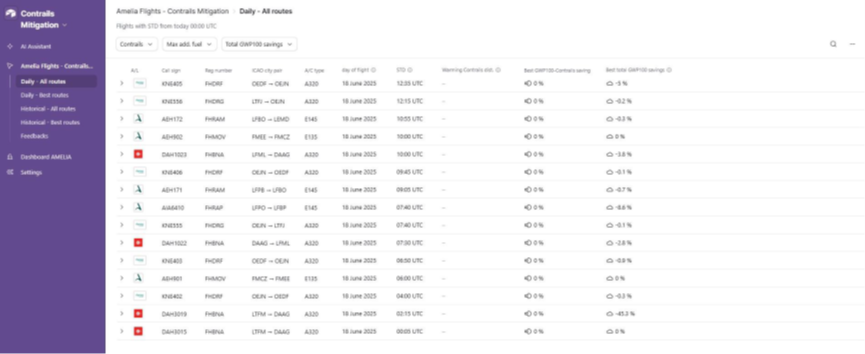

We then moved from a manual approach to a streamlined, fully integrated process in the OCC, with the goal of gradually extending it across our network, see figure 9.

Figure 9

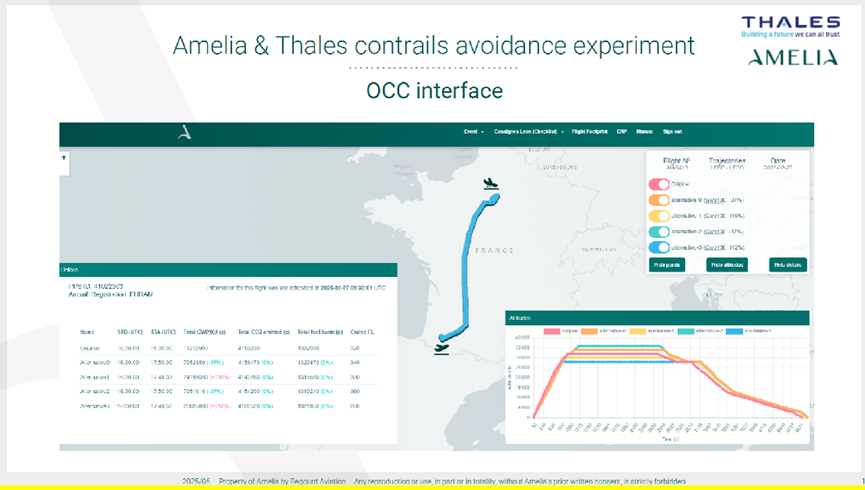

The solution is simple and efficient — it can even be used on a smartphone. Figure 10 shows a typical day: flights with contrail alerts, distance affected, potential impact, and available alternative routes. Only relevant information is presented to the OCC to minimize workload.

For example, when a contrail alert appears, the ‘Best routes’ section shows one or more alternatives that can be sent to the OCC for review. Pilots then receive a clear email with the proposed route and confirm whether it is acceptable. Once approved, the flight plan is updated and sent back to the crew. Simplicity is key.

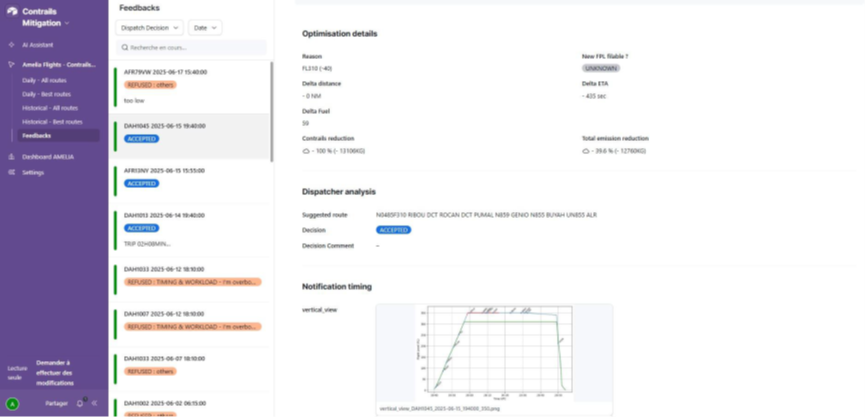

Figure 10

We also track acceptance reasons. For example, if a proposed plan is not flown, we record whether it was due to operational or ATC reasons. Optimization details are included: in one case, a descent from FL350 to FL310 (40 feet) was expected to save 13,000 kg of CO₂. This information is visible to OCC dispatchers, who can approve or decline the plan.

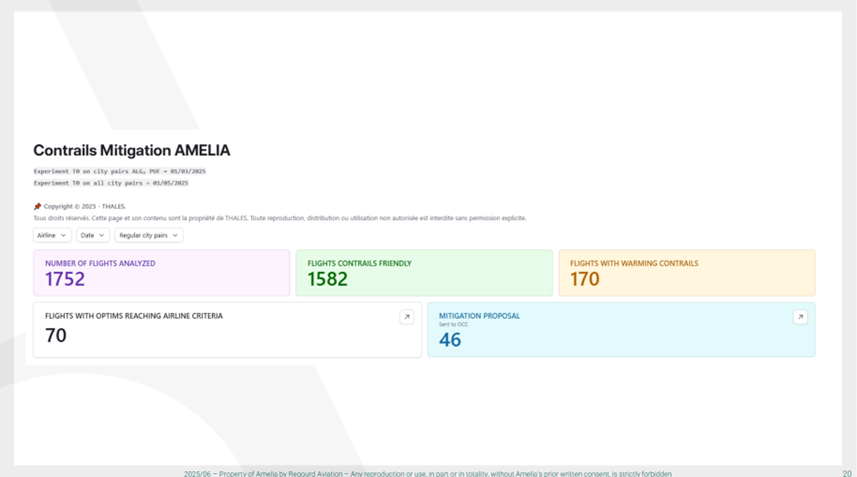

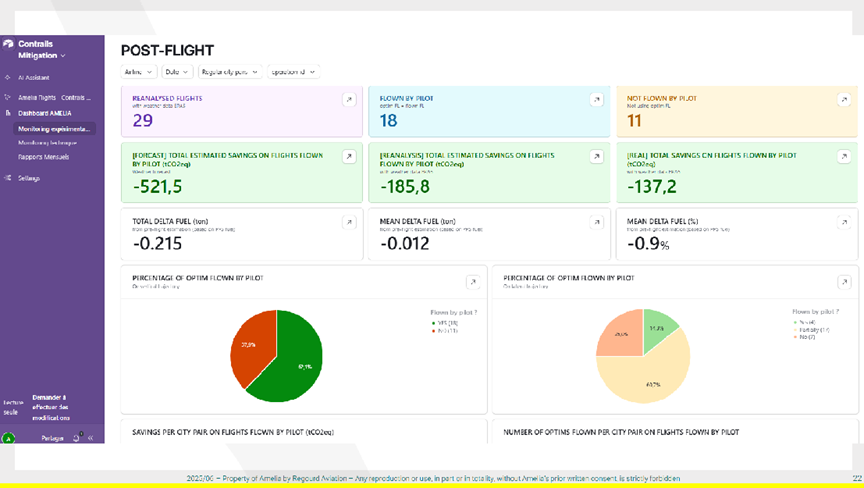

Monitoring is essential — you cannot improve what you cannot measure. We use multiple KPIs to understand performance (Figure 11).

Figure 11

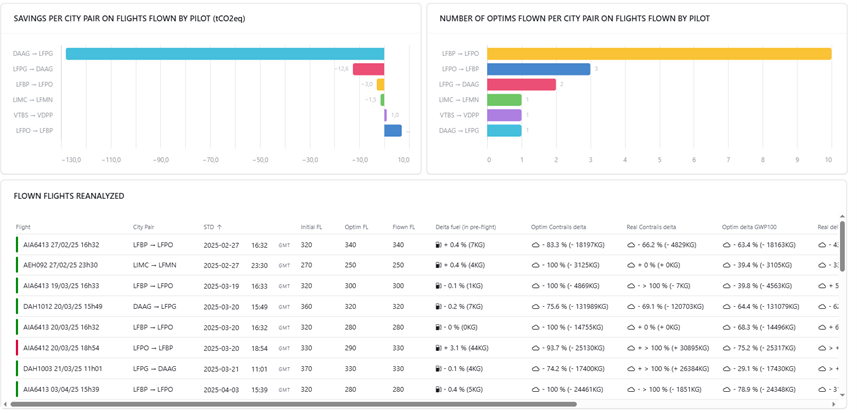

By the time of writing, contrail avoidance planning had been applied to nearly 3,000 flights, far more than the 50 flights initially tested. Many flights have no contrail risk, so no changes are needed. For flights that do, options are generated and sent to the OCC. Feedback allows us to track how many proposals were approved and estimate the expected benefits.

In post-flight analysis shown in figure 12, only 18 out of 29 proposed flight plans (60%) were flown by the crew, due to operational or ATC reasons. We compare the planned versus actual trajectory and recalculate the benefits using real data.

Figure 12

Initially, we estimated about 500 tons of CO₂ savings across these 29 flights, but the actual savings were 137 tons, about a quarter of the expected value. This shows that less than 30 flights can deliver significant climate benefits, while sometimes also reducing fuel consumption through more direct routing, see figure 13.

Figure 13

Even when a new flight plan does not fully prevent contrails, the net climate benefit remains positive, confirming that the approach is effective.

MAIN TAKEAWAYS AND LESSONS LEARNT

Keep it simple. The first lesson is that processes must be as simple as possible, especially for the OCC. Their workload is high, so every action should be straightforward and ‘push-button’ — the same applies to pilots. Complexity slows adoption.

Monitor and use KPIs. Dashboards are essential to track what we are doing. Feedback must be collected and used to continuously improve adherence to the solution. This allows us to gradually increase the percentage of pilots flying the proposed contrail-avoiding plans — from the initial 60 percent toward 80–90 percent. Even 60% from the start was a strong result.

Test and co-develop. Solutions may work perfectly in software but behave differently in real operations. Testing with OEMs and suppliers and collecting feedback ensures that the system works reliably in practice. Close collaboration and iterative development are key.

In conclusion, managing — and eventually reducing — contrails may seem challenging, but it is worth the effort for the environmental benefits and significant climate savings. Accounting for contrails allows us to analyze the total climate impact of our operations and optimize them more effectively. Continuing the deployment of the Thales solution, initiated in 2022, remains one of the most promising cost-effective approaches for reducing aviation’s climate footprint.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.