Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| A question of integrity | Paul Saunders | View article |

| Leaving and arriving safely and efficiently | Arno Broes, Partner and Commercial manager, ACFT PERFO | View article |

| The problem with implementation | Captain Michael Bryan, Principal, Closed Loop Consulting | View article |

| Case Study: Saving Fuel at Condor | Captain Frank Lumnitzer, Head of Fuel-, Environmental- and Air Traffic Management, Condor (Thomas Cook Airlines Group) | View article |

Leaving and arriving safely and efficiently

Author: Arno Broes, Partner and Commercial manager, ACFT PERFO

SubscribeLeaving and arriving safely and efficiently

Knowing the key data about an airport is vital if flight planning is to be well based, says Arno Broes, Partner and Commercial manager at ACFT PERFO.

Departure points and destinations

It has always been the case that pilots needed to know about where they were flying from and where to. It was a matter of safety, it governed how to fly the aircraft according to local conditions and what (or, at least, how much) could be carried on the aircraft. Location specific conditions such as height above sea level, temperature and pressure at different times of year, the terrain in the immediate vicinity of the airfield and a whole lot of other natural factors would all influence a pilot’s decisions. And then there were the man-made factors; length of runway, distance to taxi and layout of the airport all of which had to be taken into account when preparing the aircraft for operation. To the untutored eye, most major airports might appear the same but, in reality, there are as many configurations of airport factors as there are airports in the world. The characteristics of an airport might even influence the type of aircraft used to serve it.

For, instance, in an obvious case, the only way that BA can operate a New York service from London City airport is by using a specially fitted A318 – not an aircraft usually associated with transatlantic travel but the largest aircraft able to fly into and out of London City Airport with its short runway and near city centre location.

It might once have been the case that a pilot could carry in his head some knowledge of the airports to which he flew but, in most cases, those days are long gone. Even a medium sized operation might serve some 200 to 400 airports and, while individual pilots probably won’t be visiting all of them in any year, the airline will; so those who have to plan each flight will need information about each airport visited to be at hand and, critically, right up-to-date so that they can configure the safest set-up for the aircraft every time it takes-off, flies a route and lands at the other end.

Need to know

As well as running a business for profit, these days, flight planners and flight crew must keep in mind the three key priorities of safety, lower emissions and fuel management (the latter two are closely related). So, in addition to information about the airports visited, they’ll need to also be aware of any current regulations issues by the regulatory bodies such as FAA and EASA; these notices to airmen (NOTAMs) will often add a further layer of requirement to be taken into account when configuring an aircraft for an airport. Whether the notices are about safety, sound footprints, temporary or permanent flight path restrictions (such as avoiding militarily sensitive areas or known hazards), airport hazards, even that a Head of State might be in the vicinity; or specific operational requirements for the aircraft following an incident or accident, they all have to be taken into account when planning a flight.

Consider what information might be needed. An obvious first piece of data would be runway length which determines a range of decisions including load capacity, fuel requirement, engine power profile and, again, type of aircraft used. Similarly, the taxiways will be important factors not simply for getting to and from the runway and the parking area but also because long taxiways mean more fuel burn. The operation of the aircraft can be managed to deal with that, but without knowledge of the airport, that is going to be difficult. Height above sea level and air density will all impact upon engine and aircraft performance and all need to be understood for each airport served.

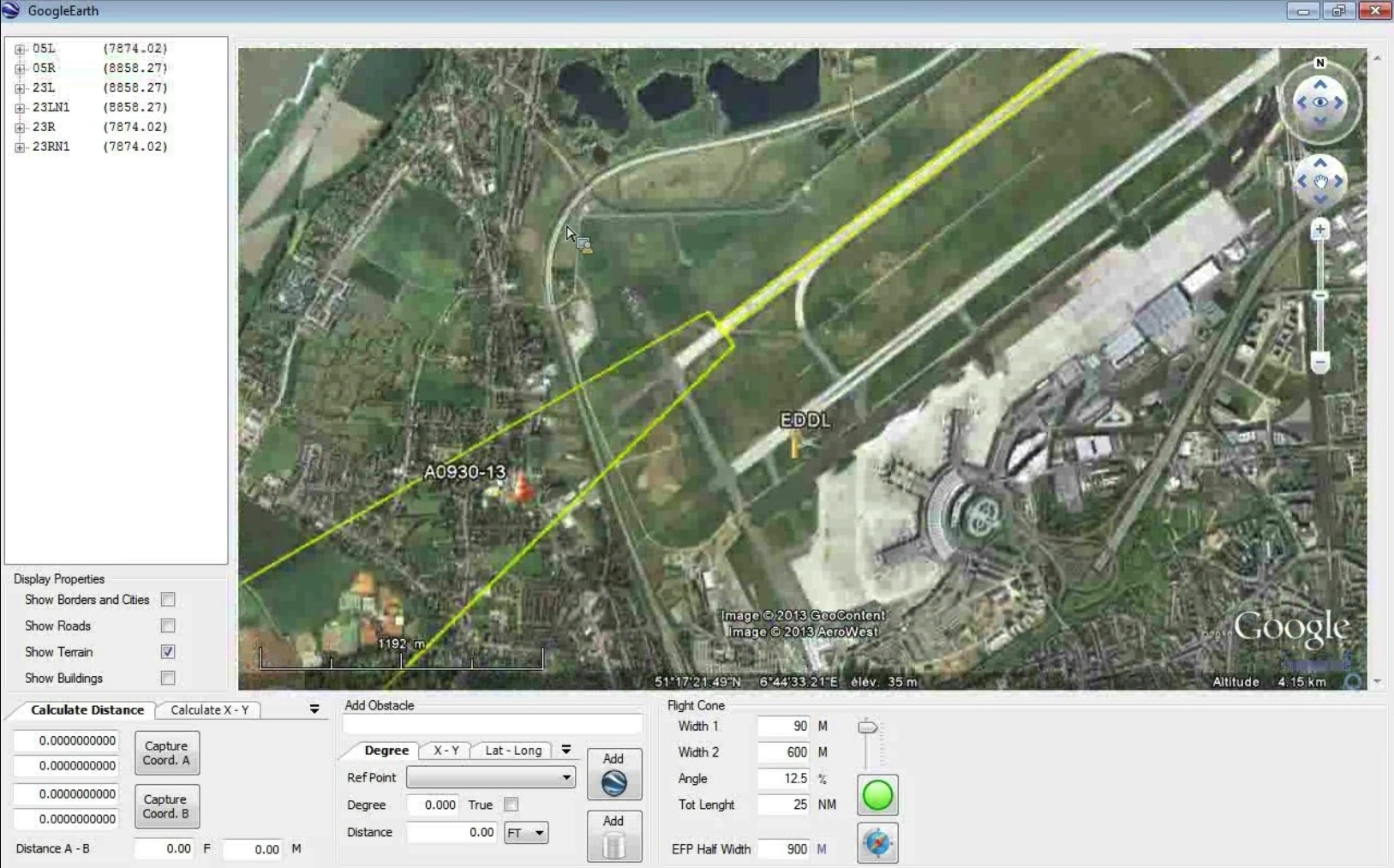

And once the aircraft is off the ground, the immediate vicinity of the airport will be important when planning the first few minutes of flight when proportionately more fuel might be burned than in level cruise. Is the terrain mountainous or level; is the area open or heavily populated; are there any other busy airports nearby and sharing some of the airspace? All of these factors need to be understood if they are to be incorporated in the flight plan.

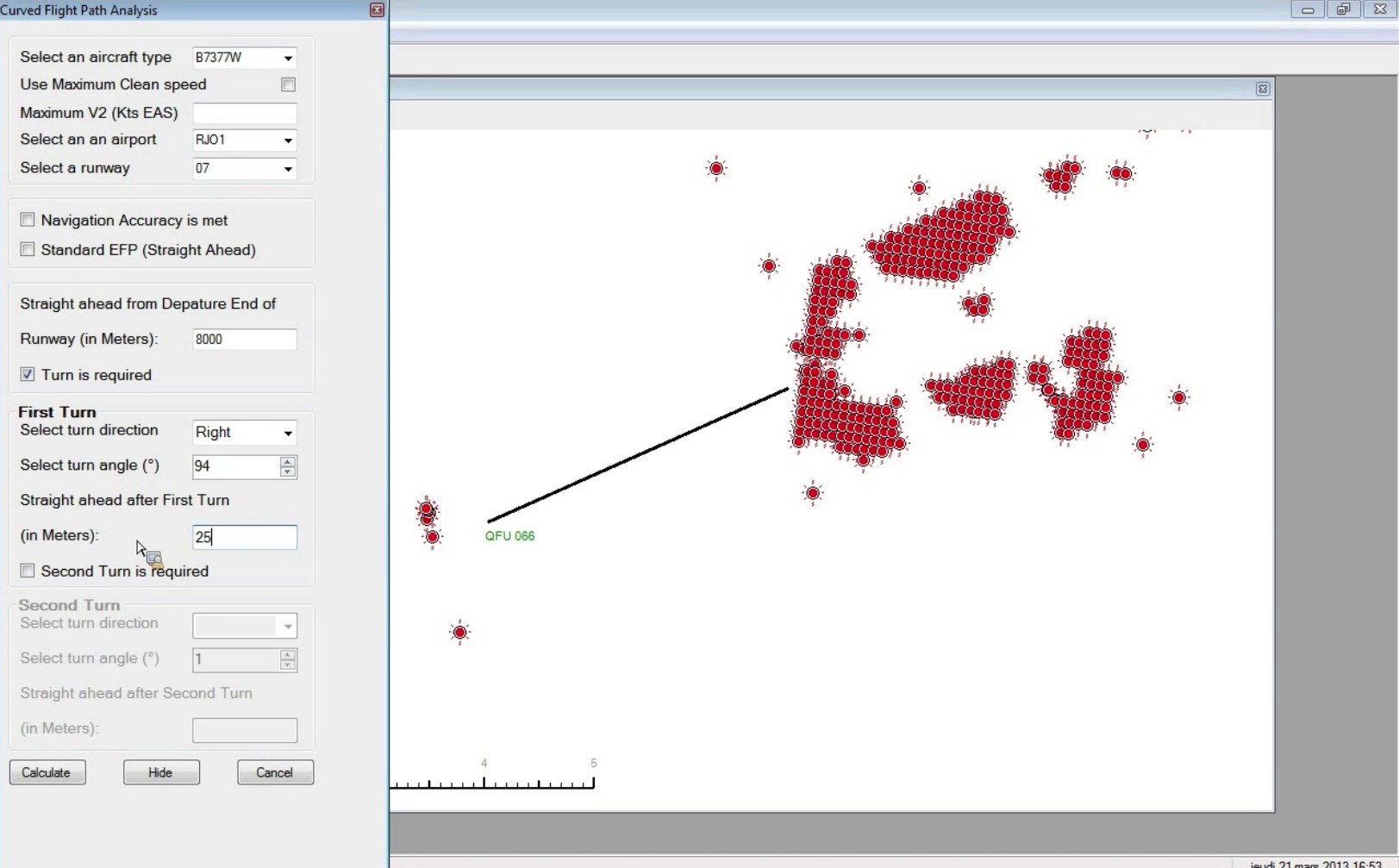

Most take-offs go without incident but every now and then there might be a problem, a bird strike, a simple engine failure or some other matter that will require the pilot to return the aircraft to the airport from which it just departed. Given the proximity of other aircraft, prevailing wind direction and the need to operate as safely as possible even in challenging circumstances, it is not an option to simply turn around and land. A proper route has to be followed and that route will need to avoid local obstacles – almost a mini, but emergency, flight path – sometimes called an engine failure path. That is the sort of information needed about every airport.

These are just a few of the more obvious factors about an airport and its proximity that will be needed to support aircraft performance.

Using the data

Consider now how that data might be used. Just the airport data will offer a support for the operational decisions around flight planning and including NOTAMs into the equation will supply most of the data needed to operate the aircraft safely, efficiently, cleanly and profitably from that airport. Accurately knowing the terrain is not just a safety issue but also can be used to improve efficiency by allowing the calculation of optimum take-off weight and engine setting to use to get the best safety, lowest fuel consumption, least emissions, most friendly noise footprint and least wear on the engine.

Outsourcing is good business

But, while this was once something that pilots or, later, airlines could do; these days the plethora of data required is both enormous and constantly variable. Not only pilots but also performance engineers and dispatchers need to be able to visualise the airport environment and environs in which their aircraft has to operate. However, do airlines really want to be diverting their resources to this task when their core business is transportation? Possibly not.

As in so many areas of modern business practice, outsourcing a specialist task such as airport data management to a business for which it is their core activity will ensure the best, most timely and most useful Airport Database with which to support key operations decisions in an airline and operator. As the above has shown, airport data is a critical part of flight planning and the management of aircraft as business units in the industry today so if it’s that much worth doing, it must be worth doing well.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.