Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| Case Study: Using data for fuel efficiency at Cebu Pacific | Francesc Torres, Director Flight Operations Technical Support & Dispatch, Cebu Pacific, and Alexandre Feray, CEO of OpenAirlines | View article |

| Optimizing your investment in innovation | Phil Benedict, Customer Strategy Development, Closed Loop Consulting | View article |

| Aeroflot’s next-generation flight planning solution | Gesine Varfis, Advisor to the CIO, Aeroflot | View article |

| Latest Innovations: Live Weather Data for EFB Devices | Toby Tucker, Portfolio Director, Innovation Programs, EFB Services, SITAONAIR | View article |

Latest Innovations: Live Weather Data for EFB Devices

Author: Toby Tucker, Portfolio Director, Innovation Programs, EFB Services, SITAONAIR

SubscribeLatest Innovations: Live Weather Data for EFB Devices

Toby Tucker, Portfolio Director, Innovation Programs, EFB Services at SITAONAIR, explains how better informed pilots make better decisions for passengers and airlines alike

THE CHALLENGE OF WEATHER

Readers won’t need me to tell them that the iPad and the Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) are now mature technologies with a growing number of deployments and an expanding range of capabilities. At the same time, weather forecasting has matured to improve airline operations’ knowledge of weather conditions likely to be encountered by their aircraft during a flight.

And it’s not a moment too soon: a growing number of weather-related events are affecting aircraft. Importantly, these are being reported in the media in near real time, but often in a manner that owes more to the need for sensation than to any consideration of balance or context. In short, around the world, everybody knows about weather-related incidents and everybody sees them, making it a topic that increasingly needs to be addressed by airlines.

For the dispatcher, there are already more and better overviews of weather information. The flight-tracking tool, for example, can be overlaid with significant weather information from various providers, such as WSI, Schneider Electric and others. This allows the dispatcher to follow what is happening, where the weather is moving, and how to help conduct the flight and provide information to the pilots.

With the trends outlined above, however, there is now a need to directly provide the pilot with better weather information, even using their iPad or EFBs to deliver electronic charting applications. Yet aside from the weather radar used for tactical purposes, significant weather charts in A4 PDF format, or in electronic format on the EFB, there is not really a tool that helps pilots. So we at SITAONAIR set out to develop and conduct trials with a number of airlines whose input is helping to improve a solution to this problem.

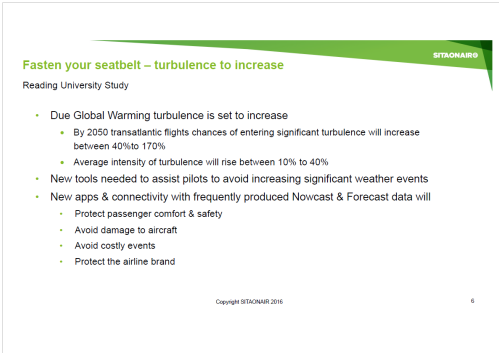

Again, readers won’t need me to tell them about global warming and the development of ever more extreme weather events. This affects turbulence, connectivity and everything related to it. A study by Reading University in the UK suggests that, over the coming years, there will be a significant increase in the frequency, and growing intensity of turbulence-related events (figure 1). So it is really becoming a topic that pilots will want more information on, using solutions that simplify the presentation of such data to give better awareness and anticipation of forthcoming weather threats.

Figure 1

As to the benefits to an airline of providing live weather data to flight crews, the case is clear. Protecting the comfort and safety of passengers is vital. It is also desirable to reduce the costs connected with weather-related incidents or accidents, and, of course, it’s very important to protect an airline’s brand.

WEATHER-RELATED EVENTS – A CASE STUDY PART 1

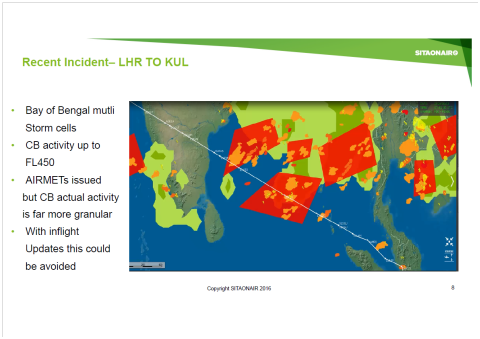

One interesting and current development can be seen in the below images and social media coverage of a recent incident in the Bay of Bengal (figure 2).

Figure 2

An airline experienced a turbulence-related incident in which 34 passengers were injured as well as six crew members. There was also minor damage to the interior of the aircraft. It happens, but in this day and age, pictures taken by passengers during the incident were posted on Twitter on landing. Such incidents can go viral these days. The figure shows the Twitter responses from media outlets requesting to use the pictures. The media focuses on incidents like these (because with the pictures they can be made newsworthy) and uses them to question the competence of airlines.

So, in addition to the damage in terms of compensation, diversions and repair costs these weather incidents cause, the airline also suffers brand damage whenever they occur and are made public, as everything is nowadays. It’s not the airline’s fault; this is the environment in which we all operate. It is unfortunate that the event in question happened to the airline, but it is something that, once it is highlighted by the press, the normal passenger, who is not really familiar with what is going on, might well conclude that the cause is something the airline has done, simply because it happened to one of their aircraft. Of course that isn’t the case, but it highlights how events beyond anyone’s control can still damage the brand of those affected.

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows analysis of what actually caused the turbulence event. Pictured is the Indian coastline of the Bay of Bengal, with the white line indicating the route taken by the flight in question. It crosses the large red ‘square’ indicating an area where thunderstorms were forecast at flight level 450, but this depiction is not very accurate. It’s a big area, and if the flight doesn’t encounter any turbulence, and the weather radar is on, it might not seem as bad as the forecast suggested. What can also be seen in the red square are some orange patches, indicating the actual active CBs (cumulonimbus clouds that will become thunderstorms), with lightning shown in yellow ‘flashes’ from Nowcasts which could be provided to the pilot at the time of the incident.

Today, weather forecasts could provide this more granular information to the pilot, with visuals, to provide a much better strategical overview of where the flight is heading, where the thunderstorms are, and where the convective areas are, to help decide whether to fly around those areas or not. That would be a lot better than just weather radar, and would show a cone up to 640 NM ahead (radar is very effective around ranges of 80-120NM). This means that if there is a thunderstorm, the pilot can take the decision about which way to go, and/or whether to prepare the cabin for turbulence. For example, the picture also shows that, on approaching this thunderstorm area, the pilot could initially see which would be the better way to turn to avoid those thunderstorms, and the weather-related incident, with all of its associated costs. The information is available today to avoid these sorts of incidents and could be provided to the pilots with the right tools and connectivity.

The question is: how to find a solution that meets the pilot’s need for usable weather information to improve operational efficiency, while, at the same time, protecting passenger comfort and using available technology?

A SOLUTION

SITAONAIR, in partnership with software company GTD, has developed an application, dedicated for pilots, that enhances what the dispatcher already sees on the ground. The difference is that it is focused on the work that a pilot does to deliver enhanced situational awareness. Even a weather forecast synchronized during briefing on a portable electronic device (PED) without inflight connectivity (mobile phone or tablet), will offer more accurate forecast data than on an A4 weather chart. This is because the pilot can visualize how the significant weather changes, using underlying forecast layers that dynamically change in the display as he drags the aircraft along the flight plan route in the app. Inflight connectivity is not necessarily a requirement, but, of course, if it becomes available, it can be used to enhance functionality with Nowcasts and more updated forecasts as they are published during the flight.

With GTD, we conducted flight tests on the solution and developed it with an airline, which showed that, for aircraft flying similar routes at more or less the same time, these tools really helped to avoid some of the significant weather events and turbulence. The developed solution is called eWAS Enhanced Weather Awareness System) and it comprises various weather forecast phenomena, such as thunderstorm, icing, clear air turbulence, and turbulence related information (not only caused by jet streams, but also caused by mountain waves, for example). All of the information, including from different weather data suppliers, is combined into one tool so that the pilot can use the one most-suited to his current need and compare information that is most relevant to him. The tool also runs on various platforms: dedicated EFBs, Windows and iOS devices including Surface Pro, iPads and even iPhone (for briefing and travelling to the airport where it can be useful, not inflight). Updates can be delivered over Wi-Fi during briefing, over 3G/4G before take-off, and also, if the infrastructure and integration is available, using Satcom or even ACARS to the EFB to leverage investment that an airline has already made.

ADVANTAGES OF SENDING WEATHER INFORMATION TO TABLETS AND EFB DEVICES

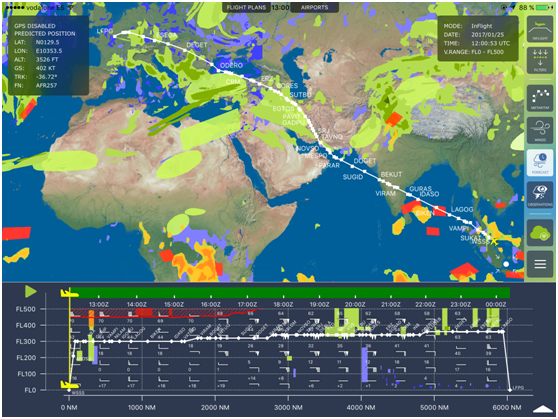

The information is delivered over a graphical user interface (GUI), as in figure 4, showing not only a plan (horizontal) view of the weather, as on paper charts, but also a vertical profile. This is helpful for visualizing the possibilities to overfly or underfly turbulence or other weather. That information is available on paper charts, but the pilot has to mentally transfer it into the vertical plane, whereas, with this GUI display, it is easier and quicker for the pilot to make the best decision for the flight. The eWAS app also ensures the pilot will have the most up-to-date data. Paper charts are generally printed a few hours before the flight preparation. The solution that we have developed is fully integrated with the airline environment. This means that routing information, such as step climbs, does not have to be keyed in by the pilot, who can simply search for the flight number and get the flight plan that has been filed with the Air Traffic Control (either from, say, Eurocontrol in Europe, or directly from the flight planning system). Whatever has been filed will also be available in the application. And last but not least, the solution takes information from various sources. Users can choose to use all of them or a particular source that they prefer as a forecast model.

Figure 4

WEATHER-RELATED EVENTS – A CASE STUDY PART 2

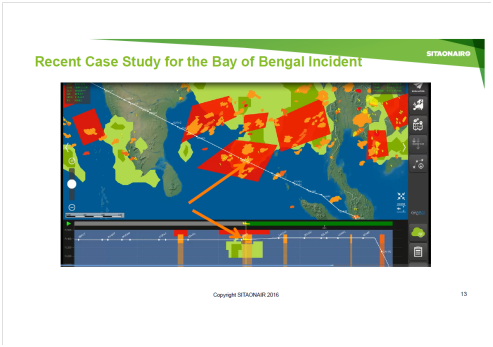

Coming back to the previous incident case study in the Bay of Bengal in which passengers were injured. Had our EFB tool been available, the pilot could have seen the view at the bottom of figure 5:

Figure 5

The arrows point to the aircraft symbol that could have been available for the pilot to see had he had access to our tool. It would have shown from the plan view that he was in an area of convective thunderstorm activity; he could have seen the real thunderstorms that were around him. The embedded radar can only warn of the first reflectivity and you cannot see the complete situation, especially the CB behind a first CB front. He would also have been able to see that, for a thunderstorm in the tropics, they cannot be easily overflown because they reach higher than normal commercial aircraft fly. Our EFB tool gives an indication of how high the weather does reach.

A SECOND CASE STUDY

Another example is of a flight from Honolulu to Manilla, where passengers also sustained injuries. It was convective thunderstorm related, and a rapidly developing thunderstorm at that. The aircraft was actually in daylight Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC), not in cloud and above one of those developing thunderstorms. On the radar alone it would have been necessary to have tilted the nose down in order to have seen something but they didn’t think it would affect their flight. With our EFB tool’s forecast the pilot would have been alerted that there was a high probability of the thunderstorms developing. Even if they could not have flown around it, they could have prepared the cabin and helped to avoid the injuries to passengers. This is not a miracle tool, but it can help the pilot make good and well-informed decisions.

ONLINE-OFFLINE

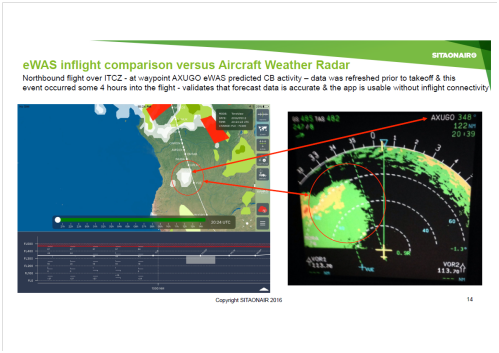

Of course, a lot of cockpits don’t have connectivity, so a pilot using this solution would only be able to take the briefing data, and might wonder whether it’s really going to help. During the briefing, the pilot would see all the forecasts along all the hours of his long haul flight. Information such as METAR, TAF, thunderstorm, turbulence, icing, tropopause, temperature and wind forecasts are available for the next 24hours. CB Nowcasting would be available for the first hour and is especially interesting for a take-off in a convective area. The pilot would have a clear view of the thunderstorm situation even in the taxi time when aircraft (and therefore its weather radar) is not aligned with the runway and is possibly not facing the convective area. All the synchronized data will be available offline during the flight. Wi-Fi or 3G synchronization between each regional flight is also an effective way to refresh the weather data. My final case study (figure 6) relates to an airline that was trialing the solution on a flight across Africa through the Intertropical Convergence Zone.

Figure 6

Four hours into the flight, the data that had been synched before take-off was already quite old. However, looking at the synched display on the left side of the figure, the white area in the red circle is a thunderstorm forecast suggesting the probability of storms. On the right of the figure is the weather radar at the time of entering the area, and, as the pilot put it, the forecast had been really good, because it had alerted him four hours in advance as to what was likely to happen – even though there was no inflight connectivity.

TRIALS

This solution continues to be developed in association with airlines who undertake trials with SITAONAIR. That helps us shape and improve the app by incorporating the ‘know-how’ feedback from the pilots as they use the app on their flights. We’ll welcome any airline or operator who’d like to conduct a trial of the solution – there is no charge for the trial – and you can send feedback to SITAONAIR through the app itself. As I’ve explained, the solution can run on most devices and airlines can freely evaluate the solution with 10 to 50 pilots. The eWAS Application is directly available in the Apple store (search for eWAS GTD) and you can request a demo account. A Windows version is also available on request.

Also, as a result of the development process, including the trials, it has been possible to regularly release new features such as:

- Wind and temperature at several flight levels;

- Tropopause;

- Meteorological Aerodrome Report or Terminal Aerodrome Forecast (METAR/TAF) for airports selected by the operational Flight Plan;

- iPhone companion device for quick access anywhere;

- Airport information (Location, ICAO/IATA codes, Runways) for selected airports;

- Automatic load of METAR/TAF for departure, destination, alternate and ETOPS airports of the operational Flight Plan;

- Increased coverage of MeteoFrance CB Sat products (Pacific, America).

In an age when moderate and severe weather events are becoming more frequent, putting passenger wellbeing at risk, as well as airline reputations, a solution that can help pilots identify risks in advance, and make better informed decisions as to how to avoid or mitigate them, will prove of real and practical value in airline operations.

To this end, Air France started to deploy this solution, on iPad, to its 4,000 pilots and managers in January 2017, seeking the benefits of a better flight preparation and a safer and more comfortable flight.

Contributor’s Details

Toby Tucker

Toby Tucker is a Portfolio Director for SITAONAIR, responsible for product strategy on EFB, CrewTab and Aircraft Data products including market introduction and operational readiness of future products. Recently Toby has designed a suite of services to solve data capture and distribution requirements for connected aircraft. He has experience in general management and business development, as well as knowledge of airline operational processes and systems. Accomplishments include the development of a web based Flight Planning solution, the introduction of an FMS Wind service promoting better fuel efficiencies to aircraft in-flight plus the set up and deployment of SITA’s EFB solution. Before SITAONAIR, Toby worked in the Royal Air Force in Air Traffic services.

SITAONAIR

SITAONAIR is the SITA Group’s nose-to-tail Connected Aircraft business, providing the complete range of products and services an airline needs to realize the full potential of the connected aircraft. It provides cockpit communications to over 14,000 aircraft with over 400 airline customers worldwide and has more than 30 aircraft operator customers who enjoy the benefit of connectivity solutions in the cabin across a wide range of aircraft types. The SITA Group is airline-owned and airline focused.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.