Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| EFB should stand for enhanced flight bag Part 3 | Sébastien Veigneau, dgBirds President and Air France A320 Captain | View article |

| Scheduling and more at Empire Airlines | Melanie Ellingson – Director of IT, Empire Airlines, Dan Perich – Manager of Dispatch and Scheduling, Empire Airlines and Tom LaJoie – President, eTT Aviation | View article |

| Modern fuel efficiency at LOT Polish Airlines | Mateusz Dziudziel - Head of Fuel Department, Kamila Giżyńska - Settlements and Analysis Specialist; both at LOT Polish Airlines | View article |

EFB should stand for enhanced flight bag Part 3

Author: Sébastien Veigneau, dgBirds President and Air France A320 Captain

Subscribe

In part 3, Sébastien Veigneau, dgBirds President and Air France A320 Captain, considers what the future holds for EFB, how pilots’ views must be taken into account and how connectivity will enable a whole range of useful and enhanced functions.

WHAT’S NEXT?

As we have seen, behind the EFB there are a lot of different functions. Some of these were initially used at the aircraft because the tablets were attached to it. But, now things have changed because tablets are mainly given to pilots to bring onboard (in some cases, known as the 2 + 2 model, airlines deploy both: tablets attached to the aircraft and tablets held by the pilots). Pilots who hold their own tablets can do much more than just executing the flight.

From home to home

For too long, the EFB has been considered as an ‘extra screen in a cockpit’. This point of view came from aircraft manufacturers that introduced EFBs as systems attached to the aircraft; supporting the pilot in execution of the mission onboard but only addressing what happens in the cockpit. In essence, the EFB is an electronic version of the pilot’s flight bag, used to carry onto to the plane items such as maps, documentation, take-off and landing performance spreadsheets… When the electronic versions of these things came along, the flight bag became an Electronic Flight Bag.

But the pilot’s mission is wider than simply the time spent in the cockpit. It is not even only from gate to gate, but from home to home. It starts well before the mission (to prepare it) and ends well after (to debrief it); and much of what it involves is not especially carried out on board:

- Procedures must be known before the flight.

- The mission should be prepared independently of the flight folder itself, by looking at regulations in the overflown countries, studying the characteristics of all airports around the possible tracks and having a good idea of the political situations of some overflown countries. In short, to consider all the environments that might affect the mission and which can be anticipated; this does not really depend on the track of the OFP (Operational Flight Plan). The idea is to anticipate any systemic threats that the mission might encounter and, therefore, consider means of mitigation.

- Finally, the pilot should consider the effective mission described by the flight folder.

During the flight, the EFB can effectively support the mission by digitizing duties and processes that were previously done manually, and with digital documentation, such as Operational Manuals or eQRH (electronic Quick Reference Handbook), electronic checklists, performance calculations, charting, etc.

Post flights reports are usually done well after the end of the mission.

Pilots expect an augmented support

Beyond that, what pilots are waiting for, is augmented support for their mission: that is, something capable of giving them information that they could not have before, not simply improving information that they could have or just digitizing it. As already stated, pilots need to be supported along their full journey, from home to home. It is not only about replacing paper processes; it is supporting many tasks around their mission that are today done via a phone call, text messages, emails, signatures on paper documents, exchanges via ACARS, etc.

Returning to the benchmark used earlier, as a pilot I want to:

- Get access to my plan of actions, updated in real-time as changes are, nowadays, common things.

- Be connected to my company with news feeds instead of being informed through the press.

- Prepare a mission by reading airport briefings and previous flight folders for the same flight.

- Get the flight folder so that I can prepare it anywhere.

- Get the exact weather situation, forecast throughout the whole flight.

- Get the preliminary load-sheet, the final load-sheet and last minute changes messages.

- Get the final reliable passengers manifest.

- Confirm fuel decisions according to last minute changes.

- Grant jump seats.

- Be notified of a deported passenger and accept or reject his transportation.

- Make reports: in particular, safety related ones.

- Read about the latest safety events in the world to keep my safety situational awareness very high.

- Prepare a training session or a line-check by reading up to date training manuals.

- And more…

Many of these use cases above were not possible with paper-only technology or without involving too many resources. How might you show on paper charts the weather situation to be expected, every half an hour of a twelve hours flight? And yet, this is exactly what pilots need.

Even if, today, the information is coded on significant weather charts produced every three or six hours, what will be the situation at 4:30Z? We don’t know exactly because the static view is not adequate to interpolate a precise situation. It offers rough data so let’s clearly state as pilots that we don’t need that anymore.

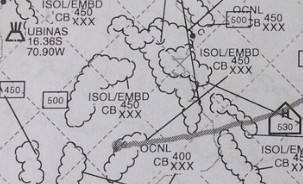

Significant Weather Chart with ISOLated / EMBeDded Cumulonimbus after take-off

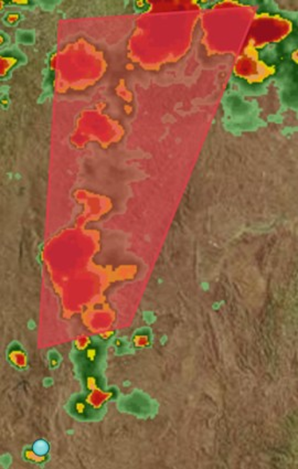

Dynamic weather interface showing exactly the isolated / embedded Cb cells as announced on Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 is mandatory in a flight folder, while Fig. 2 is obviously the one that helps pilots to take decisions well before encountering the Cbs – Cumulonimbus clouds.

In short, as a pilot, I want functions that augment my situational awareness by adding information that was impossible to get with paper processes. Tablets are more than EFBs because they are used outside of the cockpit. And with the extension of internet connectivity from the ground to the air, these tablets will benefit from continuous connectivity, from home to home.

CONNECTING

The industry is going around in circles because the business case for the installation of cockpit connectivity is not at all obvious to demonstrate. Two use cases are regularly mentioned: access to real-time or at least updated weather information, and communication with the MIS (Maintenance Information System) to postpone a technical problem on the aircraft upstream and thus anticipate its troubleshooting.

Better experience, better business case

Regarding this second use case, do we really need an internet connection for this communication of simple text information? We can do it by ACARS but do we do it? No: the point is that delivering a user experience that is much better than what is available today motivates pilots to do actions they might have otherwise inadvertently forgotten. And this is not easy to demonstrate, but that’s a reality.

Connectivity allows remote services

Why do we need connectivity? Connectivity for the cockpit is to make it possible to leave functions on the ground without impacting the operation of the aircraft. For example, should the function that optimizes the flight profile stay on the ground? Typically, yes; because this function integrates all parameters and produces a recommendation to the crew. No need for this function to be offline on an EFB. By its very nature, it needs connectivity to get the environment information updated. So, the global process should be that, without any request from pilots, the back-office should compute the best profile for the next two hours of flight, in line with the permanently updated environment conditions (weather data, other aircraft trajectories and foreseen profiles, weather conditions on arrival, number of passengers missed connections, Oceanic Clearance constraints…) and the current aircraft characteristics (Zero Fuel Weight, Fuel On Board, Flight Level, Mach…). When relevant, the new profile should be notified to pilots with the detailed strategy.

An example of a typical communication from the ground to the pilot might be:

‘We recommend that you postpone the climb to FL360 at 14:00Z and then reduce your Cost Index at 50, because the possible moderate turbulence at this level will then be behind you. Thanks to your early departure, the taxi time was shorter and your expected arrival time is 20 minutes ahead of schedule. Your OFP (Operational Flight Plan) has been recalculated because you are heavier than calculated in the initial OFP and too early on arrival. FL360 will be the optimum flight level when reducing the Cost Index to 50 to ensure an arrival closest to the H-10/H range.’

Connectivity means new services

A connected tablet is like a connected smartphone. Users of smartphones do many things they didn’t do before just because they have access to new useful functions and because it is simpler than ever. Thus, the operational efficiency gained by giving a connected tablet to a pilot and/or installing an aircraft attached connected EFB goes beyond just replacing paper-based functions. That’s why it is somehow difficult to demonstrate a business case by comparing things pilots do now with the same things they will do with a connected tablet. In fact, they will do more than they do today, so airlines should stop spending too much time trying to demonstrate an ROI (Return On Investment): it is evident that benefits will be there. The question is not ‘why’ should we give pilots a tablet but ‘when’?

Collaborating

Collaboration and information sharing will bring further improvement in operational efficiency and flight safety. On the road, sharing unusual conditions using Waze for instance brings safety. In the sky, it’s exactly the same, but we are still unable to easily share information between all aircraft in a given area: turbulences, effective wind shear conditions on final, aircraft sensed wind turning on final transmitted to the following aircraft, temperature inversion after take-off, real braking capabilities on a runway…).

Imagine a performance calculation directly powered by real weather and runway conditions, shared by other aircraft that just landed a few minutes before. Don’t you think it would be much better than trying to assess the runway conditions with this kind of message?

CYFB RSC 16/34 160 FT CL 70 PCT DRY SN TRACE, 30 PCT BARE AND DRY. REMAINING WID 100 PCT DRY SN 1 INS. 4 INS WINDROWS 20 FT ALONG INSIDE WEST RWY EDGE. RMK: TURN AROUND SLIPPERY. 1803010218 CYFB CRFI 16/34 -6C .44 1803010215 RMK: TWY ALPHA, DRY SNOW OVER COMPACTED SNOW 20 PCT, 1/4IN. DRY SNOW 80 PCT, 1/4IN. CHARLIE, DRY SNOW OVER COMPACTED SNOW 10 PCT, 1/2IN. DRY SNOW 90 PCT, 1/4IN. DELTA, DRY SNOW OVER COMPACTED SNOW 10 PCT, 1/4IN. DRY SNOW 30 PCT, TRACE. BARE AND DRY 60 PCT. ECHO, DRY SNOW 60 PCT, 1/8IN. COMPACTED SNOW 40 PCT. FOXTROT, CLOSED. GOLF, DRY SNOW OVER COMPACTED SNOW 10 PCT, 1/8IN. DRY SNOW 90 PCT, 1/4IN.

Sharing primary parameters with others may contribute to the overall efficiency of the system. The wind actually experienced by previous airplanes can inform a pilot to change their ECON Mach. But, this requires a permanent and affordable communication channel between cockpits, whether or not that involves ground relays.

Let’s take another example. In flight, we are used to actualizing the initial airports weather data we got by reading the flight briefing package. This is done by requesting METARs (METeorological Aerodrome Reports) or ATIS (Automatic Terminal Information Service) for all relevant airports around the aircraft position. We are expecting an EFB solution that, thanks to its connectivity, can update the weather data automatically according to the position of the aircraft. It seems to be something easy to deliver, but it is not yet a reality for airline pilots. Moreover, operationally interpreting a METAR takes time, because we need the context to understand the text. What are the available runways (lengths)? What are the possible approaches and their minima? What are the NOTAMs impacting the airport suitability (closed runways, instrument approaches H/S, minima…)? Without all this information, the METAR does not serve the real need which is, ‘if needed, can I land there and in which conditions? And, depending on the situation, what priority shall I give to this airport compared to others?’

CONCLUSION

Historically, the EFB has been closely attached to the aircraft and the mission of pilots in the cockpit. But things changed in 2010 when the iPad was released and was seen as a fantastic enabler for innovation in aviation operations. Tablets are now mainly given to pilots to support their mission. Airlines may still deploy aircraft attached tablets as primary EFBs onboard while the pilot held tablets serve as backup of primary means but also outside of the cockpit, as powerful assistants.

Many functions can now be developed to enhance the situational awareness a pilot should have before and during his mission, and to optimize it while being executed. Some new functions didn’t exist with a paper process. Through helping pilots in their duties, the EFB doesn’t only improve existing tasks already executed by pilots. By augmenting the information, it definitely improves safety and operational efficiency. Regulators should certainly consider this a little bit more.

In all of this, user experience is key, both for pilots that are more motivated than ever to do their best, and thus for the airline. The EFB should no longer stand for an Electronic, but for an Enhanced Flight Bag, not only from gate to gate but from home to home.

Contributor’s Details

Sébastien Veigneau

After teaching computer science and as a TRI while flying A320 and B777, Sébastien is now flying the A320 as Captain at Air France. With a PhD in Computer Science and his Air Transport Pilot License, he developed software solutions before introducing the iPad for Air France pilots in 2012. As an EFB expert, he participated to the EASA RMT 601/602. In 2017, he co-created and became President of dgBirds, AF subsidiary.

DG Birds

dgBirds is a vibrant company based on many years of experience in designing mobile solutions for professional pilots. In 2010, Air France chose the iPad as an Electronic Flight Bag for its pilots and developed some apps to support their mission. dgBirds was launched in 2017 as a subsidiary of Air France to build on this successful solution used by 4000 pilots. The business is committed to developing and marketing software solutions for any mobile business.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.