Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| Case Study: Lufthansa: Digital Flight Deck | Matthias Schmitt, Flight Operations Engineering, Lufthansa German Airlines, and Heidi Brockmann, Product Manager and Senior Consultant, Lufthansa Industry Solutions | View article |

| Keeping a track of aircraft at all times | Paul Gibson, Portfolio Director, AIRCOM, and Paul Rainford, FlightTracker Product Manager, SITAONAIR | View article |

| EFB: Data Security & Connectivity | Capt. Brian Tighe, Deputy Chairman, and Capt. Kevin McCarthy, National Training Committee, Allied Pilots Association | View article |

| Case Study: A single EFB solution for a complex business | Christian Langvatn, Pilot & EFB Project Manager, Widerøe and Wim de Munck, Chief Technology Officer, AvioVision | View article |

EFB: Data Security & Connectivity

Author: Capt. Brian Tighe, Deputy Chairman, and Capt. Kevin McCarthy, National Training Committee, Allied Pilots Association

SubscribeEFB: Data Security & Connectivity

Cyber security, explain Capt. Brian Tighe, Deputy Chairman and Capt. Kevin McCarthy, National Training Committee at the Allied Pilots Association, needs to be tackled in a structured manner

One of the challenges writing about the EFB (Electronic Flight Bag) data security and connectivity is that the issues permeate so much of today’s society. The EFB is just part of the larger problem of cyber security. So a lot of this article will look at cyber security in general, networking with the aircraft and what are the concerns of operators. We’ll then tie it all together to see how it relates to the EFB but starting with a statement of the obvious.

THE PROBLEM

Cyber security is a rapidly growing problem in the world today and there are very few segments of society that are not affected or have not been affected by cyber-attacks and their consequences: and it would be foolish to think that the commercial aviation sector could be immune to the threat… we’re as vulnerable as anybody.

The way things are

Historically, aviation systems have not been designed with security in mind; they’ve been designed with safety as their priority and efficiency. We’ve seen, as we’ve progressed from Sopwith Camels right up to modern digital aircraft, how that has changed. One of the characteristics of the modern digital age is that a lot of the networks within airplanes are not secure, they’re not encrypted and they’re not authenticated. Furthermore, as we’ve become more e-enabled, we have become a bigger target for things that could go wrong and for cyber criminals. In short, if the axiom that ‘everything eventually gets compromised’ is true, then we need a back-up plan. As operators, that’s particularly important to us because we’re the ones that bore holes in the sky at eight tenths the speed of sound.

Identifying the issues and dealing with the problem

The problem is so large and so complex that there’s no single solution and there’s no simple solution. It will require lots of people to work together because it’s impossible for any one group, leave alone one person, to get their arms completely around a problem of this size. But, if it’s that big a problem, what are we going to do about it? The first thing is to prioritize what parts of will have to be tackled first. We can, perhaps, take a lead from the old philosophical adage of, ‘How do you walk a thousand miles?’ to which the answer is, ‘One step at a time.’ But we know that in the cyber world, technology is moving rapidly, there’s just too much stuff to cover so we have to determine what is important to protect and to take care of in this realm.

Lots of regulatory agencies (EASA, FAA…) are working on this problem and the good news is that they’re working hard to keep up with what the issues are. There are Standards groups such as ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization), EUROCAE (European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment), RTCA (Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics) plus the OEMs – the manufacturers of aircraft and avionics, are becoming increasingly aware of the issue. The one group that has not given this matter a lot of attention but needs to are the users, airlines and aircraft operators; we know that many would think that, with pilots in the seats, they’ll notice and be able to react when something is going wrong; but as we’ll show below, that is increasingly difficult to achieve. So we believe that users must actually get involved with the decision making that determines what policies and what input goes into securing the networks around and within aircraft.

An overview of the cyber threat

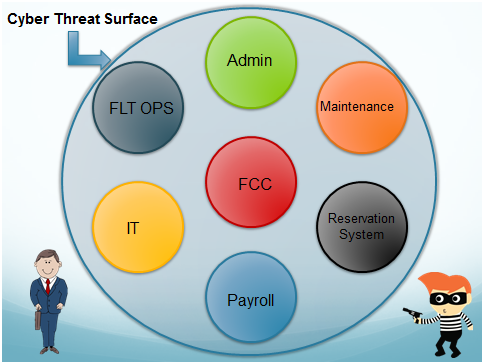

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows a bubble representing the company or, rather, its cyber threat surface. One of the things that managers are responsible for is protecting their company from all kinds of things but, for the purposes of this article, we’ll limit ourselves to the cyber threat because there lots of bad people out there trying to do things to the company, trying to disrupt the business and its processes. They are constantly looking for ways to get in, to attack; but, the larger the surface of that bubble, the harder it is to defend it all and there are lots of different avenues for gaining access. However, in a good cyber security structure, there are multiple layers as with any administrative hierarchy within a company; there are different departments and those departments have their own internal security.

Figure 1 uses just a few sample departments, not all-inclusive. There will be administration, IT, maintenance, flight ops, reservations, payroll… all the different departments. If somebody were to compromise any one of these departments, it will cost the company money. Some of them will also cost significant inconvenience but one element, if compromised, will threaten an airplane and pose the question whether that airplane can continue to fly. That is the flight control computer (FCC). We’re in a digital age where airplanes are flown by computers: pilots just make the inputs. If that computer is compromised the pilot will be the last line of defense against the malicious intent of the cyber-criminal.

Connectivity – a network for efficiency or a way in for criminals?

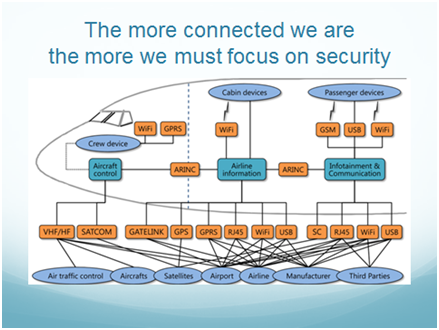

At this point, it will be useful to take a sideways step and look at connectivity which is growing across the world with 10 billion devices out there right now and most of them unsecure. In our industry, connectivity is a huge matter for efficiency reasons and that is quite understandable. Figure 2 is a diagram of an airplane and its network.

Figure 2

Because there are so many vectors potentially into an airplane, as connectivity increases, as the digital age puts increasing numbers of computers into the aircraft’s ecosphere to access different things, there is also an increased threat to cyber security. And that inner sanctum, the flight control computer, is where we increasingly need to focus to make sure that it never gets compromised. But why is the flight control computer so important? Can it be compromised; is it possible to hack into it? To answer that question, we’ll need to understand how airplanes work.

Older ‘stick & rudder’ aircraft were flown by the pilot in a fairly straightforward interaction; the pilot took actions using the controls to fly the airplane. Technology advanced with great improvements of which one of the best is the auto-pilot (A/P), especially on long trips because it made the pilot’s job easier. It was a level of automation; so the pilot was just slightly removed from actually flying the airplane with a step between his actions and the aircraft doing what he wanted it to do.

Advancements continued as flight management computers (FMCs) made navigation much easier then we entered the digital age. Now we use digital flight management computers (FMCs) for navigating easily around the world and, what happens is, the pilot programs the FMC which, in turn, tells the auto-pilot what the flight controls should do so that the airplane goes where it should. But the pilot is two steps removed from actually flying the airplane.

Coming to the most modern aircraft, which are wonderful with flight control computers making them more efficient and more fuel efficient with their lighter build, we find that the pilot is now three steps removed from flying the airplane. In just four generations of airplane, we moved from the pilot flying the airplane to him being three steps removed from the controls.

Notwithstanding the above, this article is not trying to teach readers how to fly an airplane it’s about EFB security but that, in turn is part of the bigger picture of cyber security and how EFB fits into that because it’s a much bigger picture than just EFB security.

When things go wrong

Let’s now look at what happens when things go wrong, if the systems degrade; with an older ‘stick & rudder’ aircraft right up to the third generation, the pilot can take over and still fly the aircraft even if the flight control computer and the auto-pilot have failed. However, in the latest, fourth, generation of aircraft it becomes more difficult because the pilot still needs the flight control computer to control the airplane. Some aircraft have alternate systems to deal with such failures but they are designed around system failures not malicious attack.

Although fly-by-wire aircraft, in certain cases, might have some mechanical means of backing up part of their flight controls, these backups are only intended to stabilize the airplane in flight until the pilots can recover a Flight Control Computer. These designs also vary widely with manufacture and aircraft type.

What it boils down to is that we’re looking at a culture change while looking at the problem. It’s well known that software and hardware change with new security but there are elements of that which will always have to be operational… policies, procedures and training of those that are going to be using all these things that are being designed. To illustrate where this is today and where we would like it to be, compare it to the evolution of safety in aviation as it developed post-World War 2.

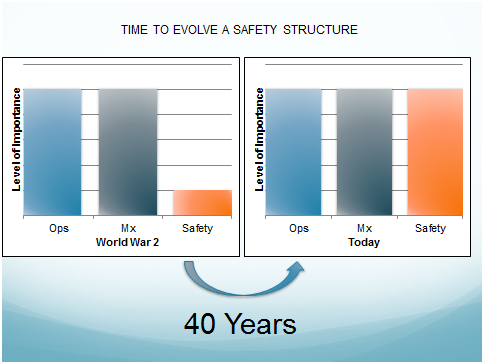

Figure 3

One of the things that Air Force safety officers are taught is how safety develops, safety programs with which we’re all familiar. In the US, during WW2, when lots of aircrews were being trained, more aircrews died in training that in combat. Safety was not part of the equation, it was relegated as something less significant behind operations and maintenance, and that might have been understandable in the circumstances. But the aviation industry benefitted from the war because technology had boomed and, after the war, became commercial. It then became obvious that safety had to become a more important part of the operation for reasons of cost and the safety of the travelling public. That change, in an evolution that took forty years, gave safety a standing on a par with everything else to make it extremely important (see figure 3).

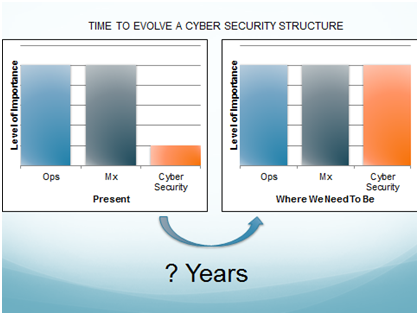

Now let’s compare that evolution with what we’re talking about in cyber security (see figure 4)

Figure 4

We’re aware of the problem but the threat of cyber hacks and cybersecurity is relatively recent. And in corporate culture it hasn’t achieved a status on a par with everything else (operations, maintenance) because it hasn’t yet had to. However, we know from banking and other sectors that you need to have your anti-virus protection fully up to date because high profile companies can suffer and have to defend against thousands of attempted breaches of their system every day.

So aviation needs to construct, just as it does with safety, a structure of cyber security within the digital environment, which includes the airplanes; and there isn’t forty years in which to do it.

WHAT IS BEING DONE?

The subject of cyber security is now getting a lot of attention from regulatory authorities, standards setters and the industry itself.

Regulation

On the regulatory level cyber security issues are addressed in the governing documents on EFBs, including…

- The FAA’s Advisory Circular AC-120-76D (draft) and EASA’s Acceptable Means of Compliance AMC 20-25.

- In the FAA’s Advisory Circular on the harmonization of EFBs, what an EFB is, is being continually redefined and what an EFB application is; that is still ongoing.

- The FAA also has a new acronym ASISP for Aircraft Systems Information Security/Protection for a working group in the Aircraft Advisory Committee on cyber security to look at what regulations and standards will be required to ensure good cyber security.

- The FAA also has an Advisory Circular (AC-119-1) that essentially establishes an Aircraft Network Security Review.

- EASA has a Preliminary Cyber Security Roadmap that continues to be improved.

Standards

On the standards side, the key standards bodies are working on the issue…

- ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization), IATA (International Air Transport Association), CANSO (Civil Air Navigation Services Organization), three of the five main aviation groups, and others have agreed to a common roadmap to align and co-ordinate their respective actions on cyber security.

- RTCA (Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics) has a Special Committee (SC-216) looking at standards on Aeronautical Systems Security and working with…

- EUROCAE (European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment) Working Group (WG-72) looking at standards for cyber security through Aeronautical Information Systems Security.

- ARINC’s AEEC (Airlines Electronic Engineering Committee) has committees and working groups that are also addressing cyber security.

The Industry

From the industry’s point of view, the manufacturers have established a security architecture review and have guidelines from a security point of view and, within the industry, the avionics manufacturers are coming up with their own applications and protocols as far as the bigger picture of cyber security is concerned.

CONCLUSION

So, wrapping it all together, there are some useful conclusions we can draw from this and to relate it to the EFB and the need for a culture change in understanding cyber security – an ongoing, evolving process. One thing that is absolutely crucial is that corporate or organizational leadership must buy in to the concept of the culture change. Everybody at every level has to understand that cyber security is extremely important because there are so many variables out there, so you have to develop a culture giving this the same importance as is accorded to safety today. Standards are important but there’s a difference between compliance and security.

Cyber security policies need to have a layered defense because we know from cyber security in general that a single firewall is not enough. One of the things we have been covering is the back-up plan; if something should penetrate to the flight control computer are the crews trained and do they have the tools necessary to save the day if need be? That has to be effected in the design of airplanes along with policies and procedures developed to handle such unusual circumstances plus in the training. Training is a large part of the cost structure of any airline and with any cost structure people will always ask what is really necessary and what is the risk of not doing it – how much is it going to cost and how much is it worth?

The point of this article is that, because of the nature of cyber, the rapid growth in the technology and the ever changing environment around it; we can’t wait to be reactive to it. We have to be proactive, think ahead and think of preventative steps, put ourselves into the bad guys’ shoes and ask what would they do and how can we prevent that.

The other piece of that is that Operations has to be involved in the decision and, typically, in some places, it is not. But when it’s not involved, the outcome is that there are groups of people managing things they don’t understand and there are other people that understand things but don’t manage – a very bad model which has to be changed as part of the overall culture change.

We’re trying to make sure that flying remains a safe way to operate. Collaboration amongst all these groups is essential. So the administrative leadership, IT and Operations have to work together.

Contributor’s Details

Captain Brian Tighe

Captain Tighe is Deputy Chairman of the Allied Pilots Association’s (APA) Training Committee. He started his flying career in the US military, flew a variety of aircraft and was involved with the development of cyber plans and security. He joined American Airlines in 1988 as a Flight Engineer then spent 19 years flying as First Officer, Captain, Check Airman and as a FAA Aircrew Program Designee. More recently he transitioned to flying international routes as on Boeing 767 and 757.

Captain Tighe is Deputy Chairman of the Allied Pilots Association’s (APA) Training Committee. He started his flying career in the US military, flew a variety of aircraft and was involved with the development of cyber plans and security. He joined American Airlines in 1988 as a Flight Engineer then spent 19 years flying as First Officer, Captain, Check Airman and as a FAA Aircrew Program Designee. More recently he transitioned to flying international routes as on Boeing 767 and 757.Captain Kevin McCarthy

Captain McCarthy is a member of the Allied Pilots Association (APA) Training Committee, and is APA’s lead Subject Matter Expert on ADS-B and NextGen technologies and the effect they will have on airline operations. He began his flying career with the US Navy as a carrier based pilot and has flown for American Airlines/US Airways for 31 years. At US Airways, he assisted in the introduction of EFB ADS-B (In/Out) NextGen applications on US Airways A330 aircraft.

Allied Pilots Association

The Allied Pilots Association (APA) serves as the certified collective bargaining agent for the 15,000 professional pilots who fly for American Airlines. Founded in 1963 the APA is the largest independent pilots’ union in the world. APA’s positions on important aviation safety- and security-related issues are based on the pilot’s perspective as a subject-matter expert. All APA Government Affairs Committee members are current line-flying pilots for American Airlines with thousands of hours of experience in large civilian transport and high-performance military aircraft.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.