Articles

| Name | Author |

|---|

Connectivity in the Flight Deck

Author: Jeffrey E. Rex, Director Engineering & Business Development, Panasonic

Subscribe

Connectivity in the Flight Deck

Jeffrey E. Rex, Director Engineering & Business Development, Panasonic explains how to leverage connectivity for real-time weather and fuel savings

WEATHER AS A COMPONENT IN EFFICIENCY

A lot is spoken and written about electronic flight bags (EFBs), connectivity, fuel efficiency and flight optimization. In this article, I want to look at tying all that together, plus looking into weather data and how connectivity can help drill down into that information. We’ll look at the two aspects of weather and connectivity; the downlink, from the aircraft, of weather data in real time which becomes like an automated pilot report and the potential uplink of weather to the aircraft; not just the same data that was downloaded, but that data enhanced with a lot of other information that can provide solutions to enable greater efficiencies, less fuel burn and improved operations.

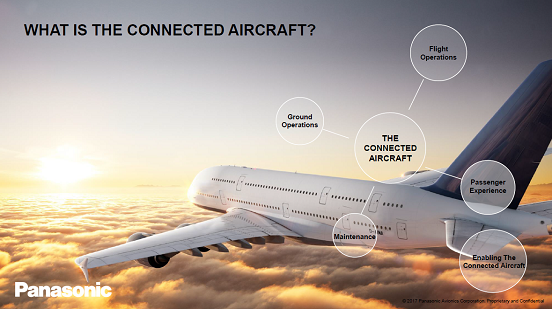

At Panasonic, along with others, we use a term ‘the connected aircraft’ or ‘aircraft connectivity’. We speak and write about the connected aircraft for a lot of reasons; it brings together four different aspects of airline operations:

- Flight operations, on which this article will focus.

- The passenger experience – readers might associate us with in-flight entertainment (the screens, on-demand movies, media streaming, on-demand content, television and in-flight entertainment that passengers enjoy) but the Panasonic name is not always apparent as there is usually an airline branding overlay on top of any system.

- Maintenance uses the aircraft’s connectivity to be prepared; to know what’s going on with the aircraft so that, for instance, it will be possible to be prepared to do LRU (line replaceable unit) swaps on the ground. Connectivity can set many processes and people in motion while the aircraft is still flying, to ensure a needed part arrives at the aircraft as it pulls up to the gate, to ensure that it goes back into service quickly and efficiently with no unnecessary time lost.

- Ground Operations; the integration of aircraft connectivity and the constant communication with it whether in the air, in approach or on the ground with all of the ground operations going on; fueling, loading baggage and everything else.

DEVICES AND CONNECTIVITY

There are multiple aspects to flight operations. In this, of course, Panasonic has its own products such as the Toughpad. But airlines have multiple needs and existing systems so that we have found the best approach is modular, to offer products and solutions appropriate to each airline customer’s needs to help them succeed. It’s important to make sure that applications and connectivity can work with any other devices and solutions. For instance, while iOS and the iPad have previously dominated this market, Microsoft Surface is now gaining in popularity. Notwithstanding the devices used, there are four main systems that enable aircraft connectivity.

Most readers will associate Panasonic with the Ku component which is the broadband Internet to the aircraft called eXConnect. There’s also an Iridium solution that enables lower bandwidth global connectivity; and there’s Cell Modem and Gate WiFi solutions that Panasonic offers with its own hardware and/or in partnership with other companies.

Satellite based internet access

Drilling down a little further, let’s focus first on the two satellite communication systems because this is where the connectivity to the aircraft and the real time data flow can help an airline. Above, we looked at four different means but, of course, users will want to optimize those means based on what the data is and what it’s going to be used for. A lot of things are not time critical; trend monitoring, operational efficiency monitoring, information gathered for historical purposes to help work out how to fly the aircraft better or be more efficient in the future: but there are certain things that need to get captured in real time and the desire to have things captured in real time will continue to increase because everyone’s expectation in life today is, ‘why can’t I have the answers now; why do I have to wait when I could get on and do what needs to be done next?’

For this, Panasonic uses two solutions. FlightLink is the Iridium based solution while eXConnect is the Ku based one referred to above. eXConnect also enables a suite of other products but it’s basically broadband internet to the aircraft. So, for passengers on many flights, this might well be the system they use, offering 50Mb per second to the aircraft, a high throughput originally intended for passengers to be able to get onto the Internet which is predominately what it’s used for today. However, now that it’s on the aircraft, airlines often think that, as they have this huge data ‘pipe’, how can it be used to enhance the operation of the aircraft?

Then there’s the issue of pilots, on the flight deck with their devices and EFBs, trying to figure out, why, if they go into the passenger cabin they can check the weather on their device but cannot do so in the cockpit. That gap needs to be bridged and Panasonic is working with partners towards manage that.

Drilling further down into flight operations and flight optimization, FlightLink is Panasonic’s system where users get to the weather reports; it’s the data downlink which feeds into weather modelling to create the flight optimization tools that airline operations use today. The FlightLink system has Iridium flight deck voice and data which is truly global, users can make calls anywhere in the world and can move data anywhere in the world. It is L Band connectivity, not like the Ku system which is a big pipe; L Band is a narrow pipe but always available, so airlines use it for ACARS, safety communications and other things. Inside this system is also automated aircraft reporting and, included in that functionality is flight tracking that’s compliant with the ICAO requirements for normal and abnormal tracking. The third leg of the FlightLink system is the atmospheric data capture which is the weather downlink of which more below.

GATHERING AND APPLYING DATA AND INFORMATION

Acquiring data

But first, let’s look at how that weather is downlinked. Aircraft can be equipped with sensors which are constantly gathering data and constantly streaming it through the Iridium system. There are very short amounts of data, ‘short burst data’ in the Iridium parlance, and it’s constantly streaming that down to a supercomputer where all of that data is pulled in, quality checked, checked against other data, checked against satellite data and checked against balloon data before Panasonic does its own evaluation against its quality models. That data is then assimilated into Panasonic’s unique weather models have more data to support a self-fulfilling cycle; if there is more data and better data it’s possible to create better models with higher resolution. Panasonic then works with partners to generate various model outputs for different industries.

Some uses for data and information

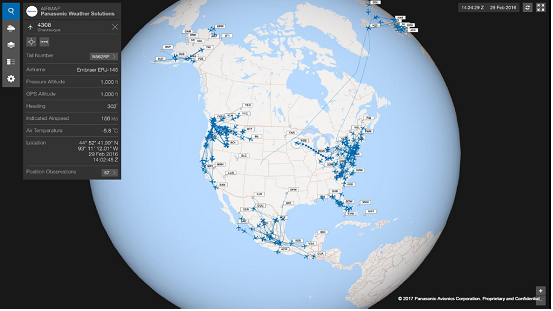

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows what the system does with a couple of airlines on screen through a flight tracking application but, in addition to flight tracking, it’s also a satellite communications interface with other screens and other layers where users can do messaging, voice communications (just select the aircraft by touching it on-screen) and, at any time, select an aircraft; so in figure 1 there is one aircraft selected, roughly in the center of the screen, which is circled and its flight path marked as a number of dots which could represent a number of observations; weather, position or both. Users can select one of the dots to see the information behind that dot. Select the aircraft itself to get real time information that has come from the aircraft in the past minute or so.

This application also enables alerts, such as flight plan deviation alerting and alerting if it’s been a while since there was any communication from the aircraft (‘No-Comms’ alert) which looks to the ICAO requirements for flight tracking; plus other alerts that might be tailored to the airline such as ‘fuel on board’.

Additionally, reporting intervals can be adjusted remotely, so they don’t require any activity on the aircraft. Once the system is on the aircraft, from the operations center the reporting interval can be adjusted. So, say it’s set at a default for every fifteen minutes for position information and tracking; when the aircraft flies into a new area that requires reporting every five minutes or simply that the airline decides that it wants to know where the aircraft is every five minutes, that be achieved remotely with a confirming message to the aircraft.

Additionally, when the aircraft is highlighted, the user can look to the left of the screen for various drop-down screens such as the general one shown or there’s also one to show all the weather information coming off the aircraft.

Creating a better forecast

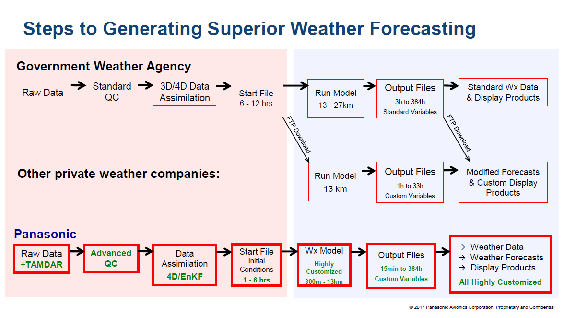

So, those weather parameters are what really help to create a better forecast, putting the highest emphasis on the highest value data. The system doesn’t start with Government weather output, valuable though that is. Because the system has access to extra data coming off aircraft in real time it is able to complete a different level of quality control and make better use of even the government data. Panasonic’s system does custom modelling, leveraging the skills of a group of scientists, engineers and meteorologists who have worked out how to maximize the output of the models, how to maximize the resolution and get the best answer by ingesting the best data. It’s a multi-tiered problem that the system is trying to solve (figure 2).

Figure 2

One tier is getting better data on the input side and that’s the TAMDAR (Tropospheric Airborne Meteorological Data Reporting) data or the data coming down from the aircraft. Most weather agencies predominantly use data from weather balloon soundings plus satellite data, ground observation data and other sources. To that, they apply a standard quality control process before easing the data into a 3D or 4D data assimilation – the difference is in whether or not time is included – to create a ‘start file’, the initial conditions of the atmosphere, a picture of what everything looks like. From there it’s possible to run a model and create output files leading to standard displays of weather such as one might see on the news. There are two places where private weather companies can pick these off: download the start file from an FTP site and run their own model, something that is fairly common, to create their own output files and customized products for the industry they serve. Also, the output files can be downloaded from the FTP site after the models run by the Government for the weather company to just change the display.

Panasonic has changed the process by starting with the TAMDAR data as well as the raw data from the Government. And because the data’s there, Panasonic is able to quality check data in an advanced way that enables them to make more use of the government data than the Government does because, with aircraft collecting TAMDAR data, it’s possible to better validate satellite data and make more use of it – hence the Advanced QC. There follows a 4D assimilation process to create Panasonic’s own start file of initial conditions. So, when a model is run out of this data, it starts from a better more high definition base. For the back-end, Panasonic works with partners who have already invented and perfected an output and display, for instance Safety Line’s Climb Optimization tool (see below).

The primary contributor to most weather forecasts is still weather balloons launched twice a day (00:00 and 12:00) at fixed points around the Earth which is good and bad. Balloons are launched from different but fixed locations and so might miss a lot of the weather between locations and, since they’re launched at 00:00 and 12:00, they also miss key times such as mid-afternoon in North America when a lot of convection problems can create big storms at certain times of year. A lot of that missed area- and time-related data can be picked up by aircraft. Every time a TAMDAR equipped aircraft takes off or lands, it creates a replication of balloon data but at a higher resolution with turbulence as well as temperature, wind and humidity plus icing information. It offers higher resolution and more information augmenting the balloon system.

The unique data analytics undertaken by Panasonic is the ability to pull together all of the different data and be able to make more of that data. We also work closely with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado and some European agencies such as ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) and the UK Met Office to work out how to best create a weather model that maximizes the availability of all of this data.

APPLICATIONS IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION

For the aviation industry, all the above means that there is a higher resolution forecast available which is useful in two contexts; for Flight Ops and pilots in the near-term and real-time, and to the AOC (Airline Operations Center) for the same reason. But, stepping back, they’re also useful for operational planning 24 to 72 hours out – where users are trying to map out their next day or two or, on a flight, their next six to 12 hours.

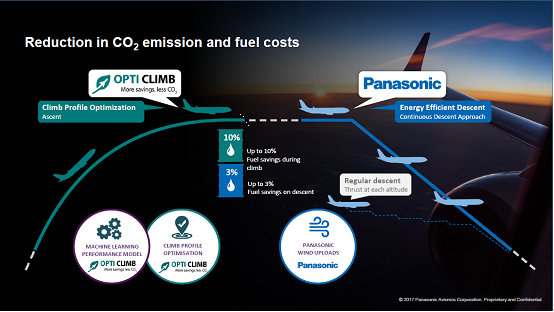

It was mentioned above that some Panasonic outputs are used by a partner Safety Line for their Opti Climb, climb profile optimization product. Flight optimization is a key area where weather services are used by a number of airlines around the world. Flight optimization is useful because it doesn’t need someone to sit down and interpolate the whole forecast, figure out what impact it will have and still have all of the subjectivity that an individual interpolation will carry. It’s about… There’s a flight plan; there’s a profile; and there’s a wind grid that’s really high resolution; so, how can that all be best pulled together to help fly an aircraft where we want to fly it while burning the least fuel?

Figure 3

The OptiClimb product (figure 3) offers up to ten percent savings which is really powerful considering that, during the ascent, the aircraft is typically at full thrust or alternating with a high level thrust. But that also makes the opportunity to gain most value with respect to fuel burn. At the other end of the mission, the descent is also something on which we have been focusing for years and, of course it’s another part of the fuel management equation. But the aircraft already has a low throttle setting during descent so the opportunity for improvement is not as great as in the climb.

Panasonic is also working with Safety Line to apply the weather data in En-Route Flight Optimization which is interesting; it’s a little trickier because it can use the backward looking data analytics with which readers will be familiar or it can be integrated with a forecast. Integrating it with a high resolution winds forecast is key to getting the right answer because, the higher the resolution (say, winds at every one thousand feet instead of every five or ten thousand feet) the easier it will be to pick an altitude that is best to fly. That’s also how the descent algorithm works with, say, forty wind speeds during a given descent path from 40,000ft to the ground; the system is able to grab the two or three best fit spots to go into the FMS and be uploaded into the flight plan vis ACARS. So it’s easier for the pilot who sends down a flight plan pre-descent, has it run through the model where new way point/descent plan is produced for display on a screen in the cockpit where the pilot can choose whether to accept it or not, whichever he deems makes more sense at the time.

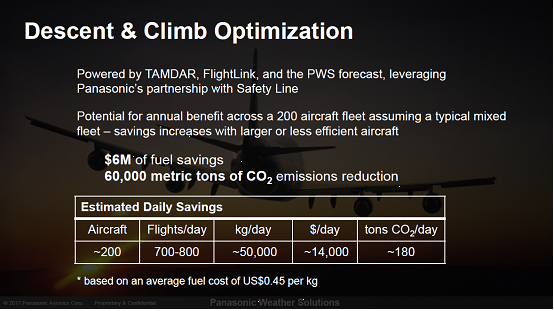

The last example of what can be achieved (figure 4) is pretty conservative based on Panasonic weather calculations with the Safety Line solution to show a good base line for discussion.

Figure 4

Of course, the calculation can be tailored for a specific airline or trials can be run with airlines to validate the system and see whether it can produce better numbers than they have previously achieved. Figure 4 is what would be seen for a flight optimization solution implemented for a typical airline with a mixed fleet of 200 aircraft (narrow- and wide-bodies) and 700 to 800 flights per day. This shows how the benefits would add up with significant CO2 reduction – very important in Europe with the advent of carbon trading – and, more importantly, the money saved at about $6million a year for this example.

A UNIQUE APPROACH

With the additional demands on data these days, the approach of running a full model and data assimilation, not just running a forecast, is in tune with the times. Panasonic does a lot of foundation work behind the forecast with a lot of ‘super-computing’ involved and then running the forecast to be able to provide output to Panasonic’s partners and create solutions for customers. Today, as the only private entity in the world with a custom-developed and operational global weather modelling platform, Panasonic Weather Solutions is working with leading airlines and operators to improve operational performance and passenger safety, as well as become more environmentally friendly due to reduced fuel burn and CO2 emissions via flight optimization.

Contributor’s Details

Contributor’s DetailsJeffrey E. Rex

Jeff serves as Director of Panasonic Avionics Corporation, leading Panasonic’s efforts in business and product development for the company’s advanced flight tracking, flight deck satellite communications, and aviation weather solutions. Prior to Panasonic Avionics, Jeff was Vice President Engineering & Product Integration with AirDat and Vice President for L2 Aviation. He graduated from the University of Colorado with a Bachelor’s degree in Aerospace Engineering and a Master’s degree in Engineering Management, completed business program studies at IMD, and is a certified Project Management Professional.

Panasonic Avionics

Panasonic AvionicsPanasonic Avionics collaborates with over 300 airline customers to develop inflight entertainment and communications (IFEC) solutions, based on state-of-the-art technology, connectivity, and industry know-how. Every year, more than 500 million passengers enjoy an entertainment experience flying onboard Panasonic-equipped aircraft.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.